Dearest Alex,

The struggle has been long, the battle waged and won:

victory is in my grasp! The Spotted Owl has landed and marked its place

in the pages of "AIMH". Finally!

Two weeks (from the moment of research to this day), but

the two page-spread is finally, finally, FINALLY done! Ahhhhhhhhh, it

feels good. If I was not getting over a cold, I might jump up and dance

a jig--maybe I'll dance a jig anyway (if I can figure out what exactly is

"a jig").

However, more to the point:

As I was drawing, I remembered how often friends, family,

strangers (mostly non-artistic types), asked me how I do what I do. Art

to non-artistic types seems like magic; there is a curiosity that thirsts for

knowledge, explanations, the naked need to "see behind the curtain".

So, I said to myself: "Why not?" Why not show everyone

exactly how I create what I create. There really is nothing to hide.

Now, be aware that every project requires its own approach.

Approaching an illustration is different from approaching a painting.

There is even a difference between approaching one style of illustration

and another. Since I do not have examples of every work I have ever done,

what this blog will show, as the title states is the "Anatomy of

"AIMH" Illustration"--the way I illustrate my first ever picture

book--which may also answer the question: "Why it's taking [me] so long

[to get it done]?!"

Step 1: The Idea

It doesn't matter what you wish to create, any creative

process begins with an idea. Ideas can come from anywhere. I get my

ideas when I sleep (that is why I keep a notebook next to my bed to jot down

clips of dreams, before they vanish upon fully waking), when I'm watching television,

reading a book, taking a walk or a shower... It comes from the ether,

netherworld, Neverland, Whateverland... Once I would have said it may

even be whispered to me by the Muses, but after recent researching of Greek

Mythology I have discovered to my shock that even though Muses are goddesses of

the arts, not one of them is a patron of visual art. It’s true—look it up.

The idea for “AIMH” came to me sometime in 2008 from a

common, Serbian saying disparaging one’s messy, shaggy hair. I think it was my mother who looked at me and

said: “Vreme je da ošišaš tu šumu sa glave.” (“It’s

time to cut that forest on your head.”)

An image of a forest growing on my head intruded upon my thoughts, and

that crazy little artist in me asked: “What if…?”

That’s how it all began.

An idea is a fluid thing; it changes, it grows, it sometimes dies... This idea did not die. It did not come to me at a convenient time,

because in 2008 I was working on someone else’s books, as well as finishing the

last few assignments for Art Instruction Schools. However, that little idea would not leave me

alone, and in my spare time I wrote down the poem. When my grandfather died, and I stayed in

Serbia to console my grandmother, I sketched out the entire book (it kept me

from losing my mind in grief).

Step 2: The Concept

The Concept in this case is the idea written and sketched

out, a visual representation of the entire picture book. These sketches were very rough, because I did

not know the exact appearance of my characters, nor of the animals I would

use. At that time they were more or

less blobs floating around in my mind and as I drew I drew upon my memories of

the images I saw. Unfortunately, I do

not have a photographic memory, so those images were rather hideous.

Step 3: The Poem

I wrote out the text for my picture book. Even though it is not exactly a poem, I keep

calling it a poem because it is written in verse. After many, many rewritings, I have a

version I’m 85% thrilled with. I still

think I may make some improvements to the text and the flow, but it works

pretty well as is. Since the rough ideas

for images are established and I do not see them changing, I began to

illustrate.

Step 4: Illustration

And here we are.

How do I illustrate?

1.

The Concept Sketch

As I have already mentioned, I’ve

created the entire picture book mock-up (The Concept), so I have a sketch to

begin from.

Bellow, you can see this sketch.

However, this sketch is very crude,

so--

2.

Research

I went on the Internet,

downloaded a bunch of pictures, and read several texts on Spotted Owls.

3.

Thumbnails

I got this image in my

head, very different form the rest of

the pages in my book; but since this is my book (I’m the editor, publisher and

art director), I decided a change may be exciting. An unexpected visual disturbance may jolt my

readers, hopefully pulling them away from the hypnotic draw of similarity.

4.

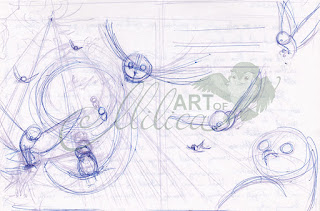

Roughs

Once I chose a thumbnail I

liked, I redrew it on the regular 8.5’’ x 11’’ paper, trying to keep true to

the ratio of my book. I did several

roughs, and bellow you can see two of them.

I added more detail to the rough

and scanned it into my computer.

Using Photoshop I sized the

drawing to fit my 14’’ x 17’’ layout drawing pad.

Then I traced the images on my “light-table”

(every animator has one, maybe next time I’ll remember to take a photo so you

can see my tiny setup), redrawing as I traced with a purple col-erase pencil

(the difference between col-erase pencils and regular pencil crayons is that they

can easily be erased).

When I was satisfied with my

drawing, I drew over it with a blue ink pen, again making changes and adding

detail.

Problem: How many talons does

the spotted owl have?

I could not tell from the

pictures. Sometimes I think there are

five, sometimes four…

Solution: When in doubt go with

design. This is not a book about owls,

so in the end I choose 4, because it just looks better. (Even though I drew five on the cover J.)

Then I scanned in that final

drawing.

In Photoshop I manipulated the

images, cutting and pasting nearly every owl until I was satisfied with my

composition. I added text, sized the

drawing yet again to fit two 11’’ by 14’’ rag drawing papers I’m using as my

final medium paper, and printed them.

Since, I do not have a desk-size

light-table and my maximum drawing size is 11’’ by 14’’, I sometimes have to

split my art into sections. In this

case, I split it right down the middle (where the seam would be).

I redrew each of the two

sections on the layout paper again and this time spent more time and effort

cleaning up, because this layout drawing is the drawing I will use to trace the

final image onto my rag paper page.

(I have no idea where the second half went.)

I do this (preferably when it’s

dark outside—no trouble there, considering that I have not seen the sun more

than once or twice this past week) with a crow-quill nib and acrylic waterproof

sepia ink.

Once my drawing is done, I let

it dry overnight—just to be safe.

The next day, I attached my pages

(using the deep green painting tape) to a wooden board. This keeps the pages from wrinkling as I

work. (Note: with watercolour paper, you

may need to “stretch” the paper, but this paper is thin enough that simple taping

works.) I choose my brushes, I filled up

two containers of water (one for dirty water, the other for dipping the brush

cleaned in dirty water into clean water, before choosing another colour),

plastic dishes (these allow me to get very clean washes, because the pigment

settles on the bottom of the dish, and I paint with coloured water left on

top), paper towel and watercolours (Yarka watercolour cakes in this case).

5.

Painting

I paint. I paint in washes, layered one on top of

another, to keep my image from going muddy.

It is very important to let the paper dry in between, because if you go

over a colour that is not completely dry it will “bleed”—creating more mud.

I decided to paint the

background first, because I wanted the owls to get somewhat lost in it, and in

general, it is always better to paint the background first, because painting

around deeply saturated characters is a nightmare, and painting together with

characters may result in unwanted “bleeding”.

Sometimes I would choose my colours

by painting my final image digitally in Photoshop before repainting it with

watercolours. This way chances of errors

in tone and hues are almost non-existent.

However, I’m running out of time for this project, so I skipped this

step.

It took days (maybe a week, can’t

remember the day I started though it is here in the blog) to paint this,

because I had to allow colours to dry completely from time to time. Getting darker tones by doing washes takes

forever, but the plus side is you get a very tree-dimensional image. It looks even more three-dimensional in real

life.

I also painted using very small

brushes (mostly #4 round), because I found that large brushes absorbed too much

water and paint, and therefore were not good for precise work such as leaves,

texture on the tree, feathers, etc.

6.

Redrawing

During painting the drawing

details would get lost, so when I was done, I redrew the owls and parts of

trees with the sepia ink again.

7.

Highlights

Most of the time, I add

highlights to the eyes using a small brush and white ink. Once that is done, I leave the work to dry

overnight.

8.

Final Scan

The next day (in this case

today), I scanned the paintings and opened them in Photoshop. I proceeded to attach the paintings

together. Despite my best efforts to

create a seamless edge, I inevitably have to use the cloning tool to eliminate

the joining line and add or erase bits of the painting to create a seamless

effect.

Finally, I sized the drawing to

a proper ratio and adjusted the text.

So, that is it.

The image is ready for printing.

I may have to adjust printing tone and the image depending on the printer,

but I consider this done. Now, it’s time

to move on to the next two pages.

Write to you later!

M

No comments:

Post a Comment

Abuse in any from will not be posted or tolerated.